Exploring into the ancient water wisdom of Jaipur Rajasthan, India.

Anubhuti Chandna

2019

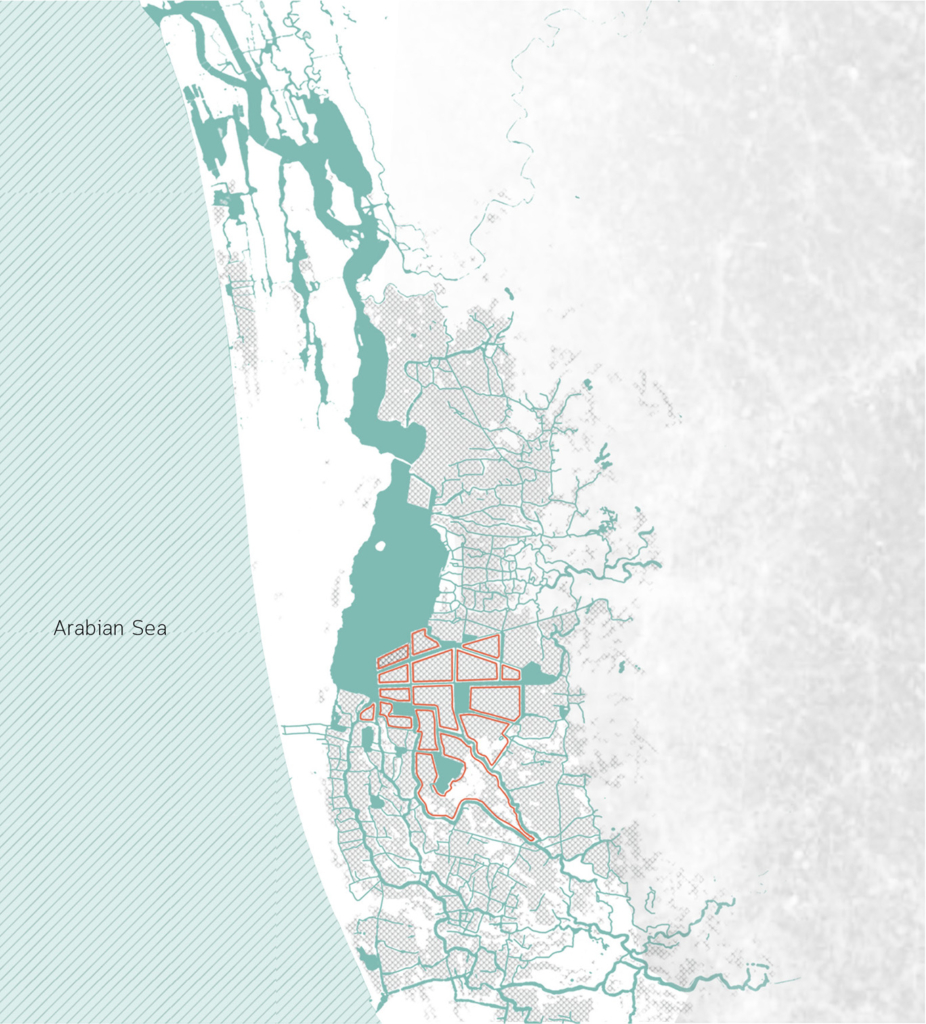

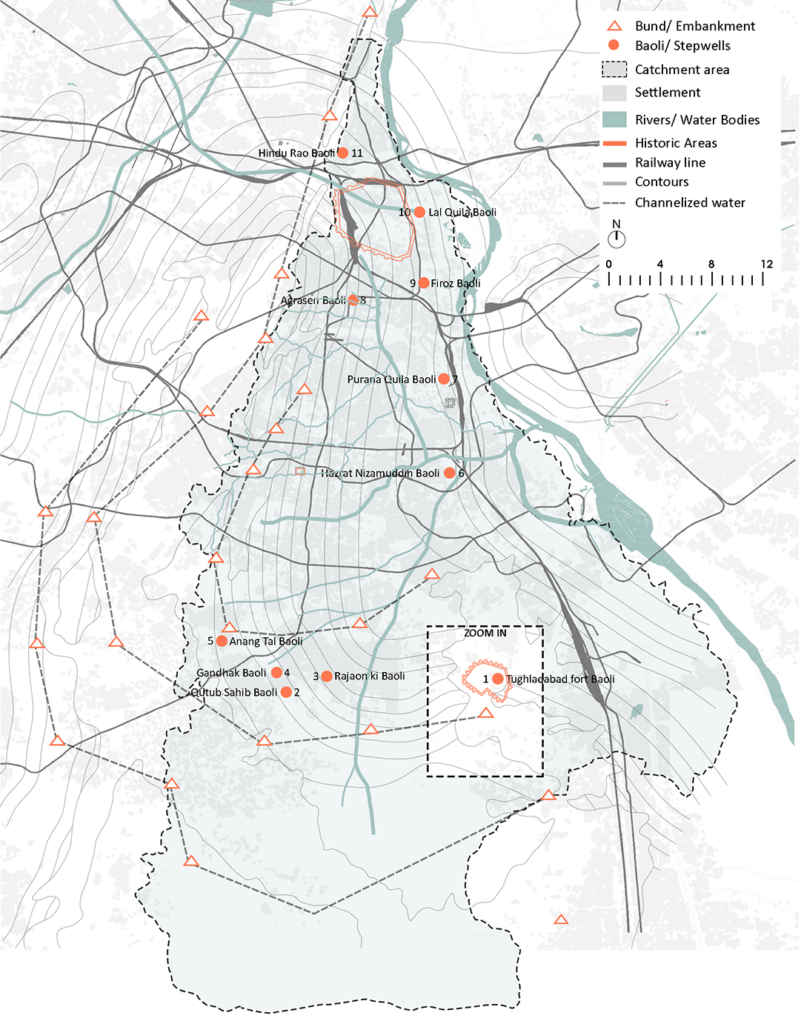

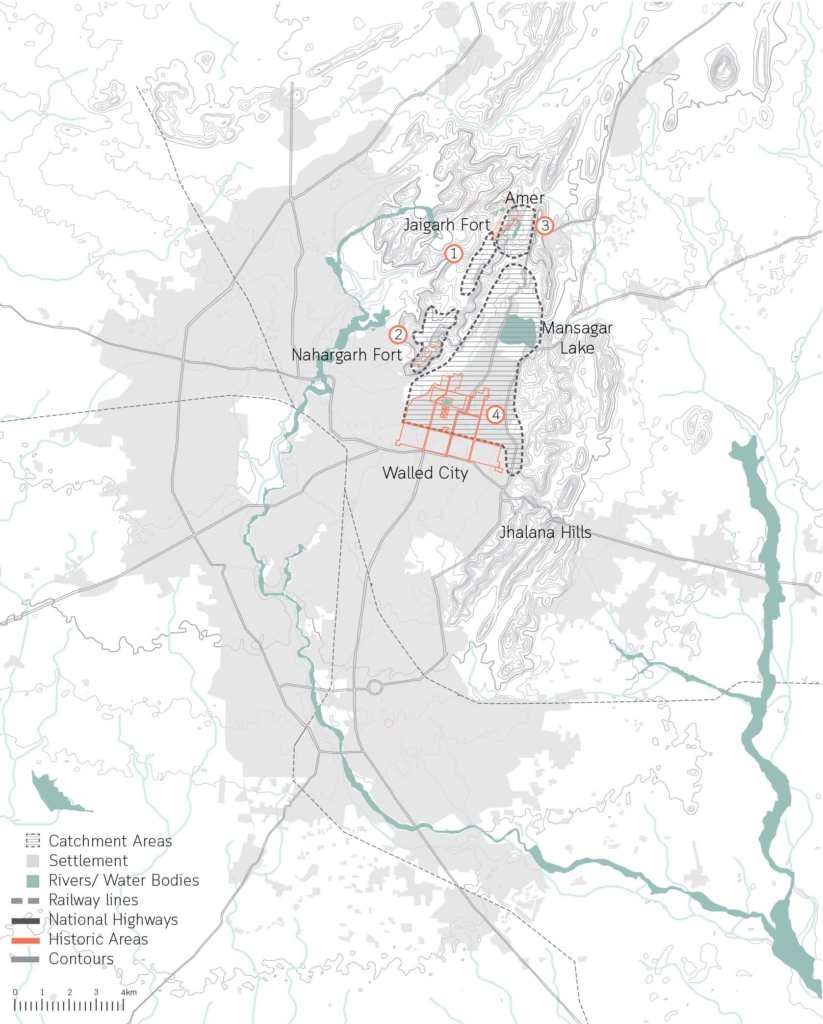

Jaipur is one of the first planned city of northern India based on the principles of “Shilpa Shastra”, in fact “Jaipur clearly represents a dramatic departure from extant medieval cities with its ordered, grid-like structure – broad streets, criss-crossing at right anglese, earmarked sites for buildings, palaces, havelis, temples and gardens, neighbourhoods designated for caste and occupation” (UNESCO, 2015).

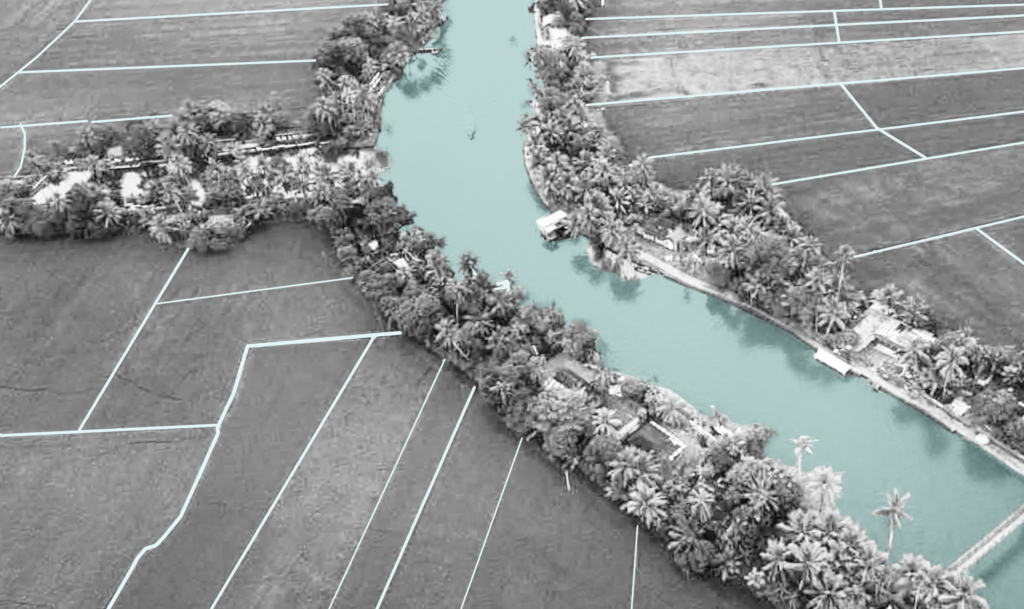

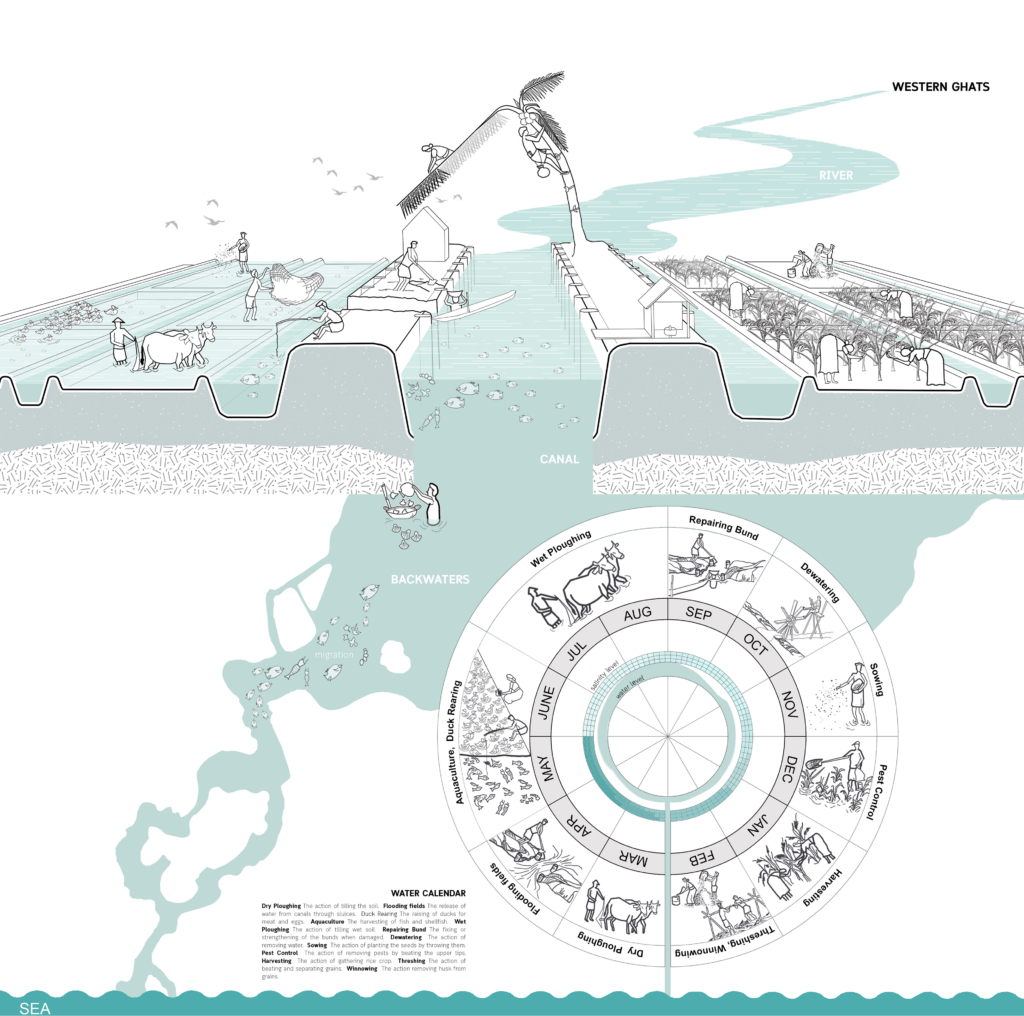

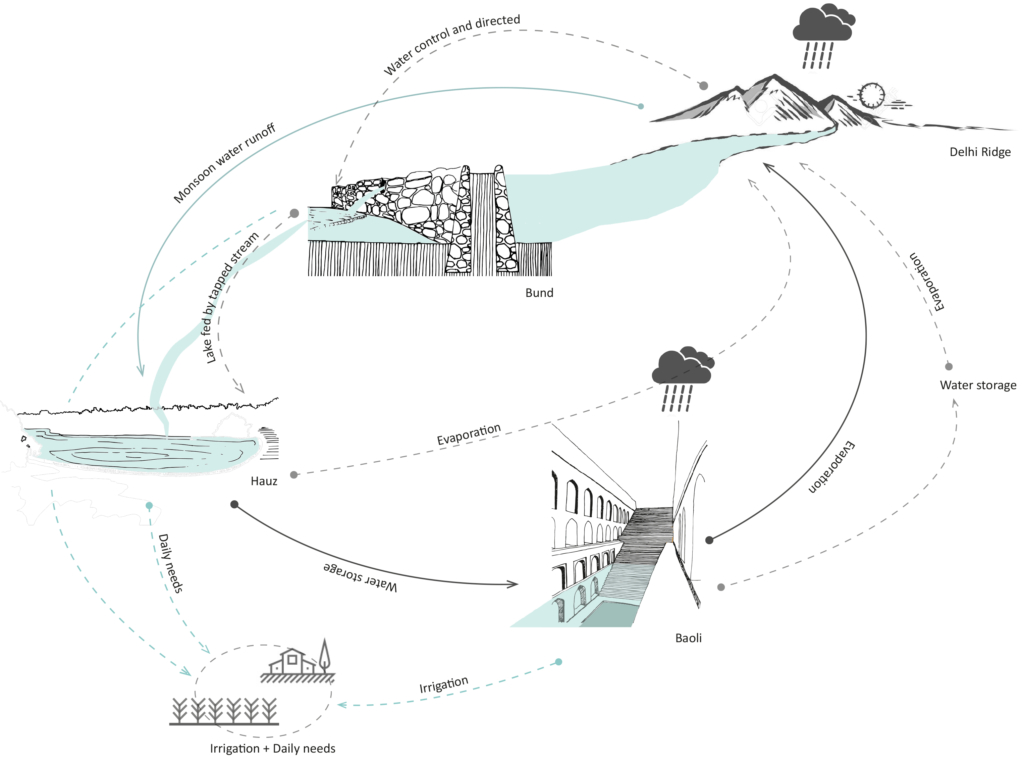

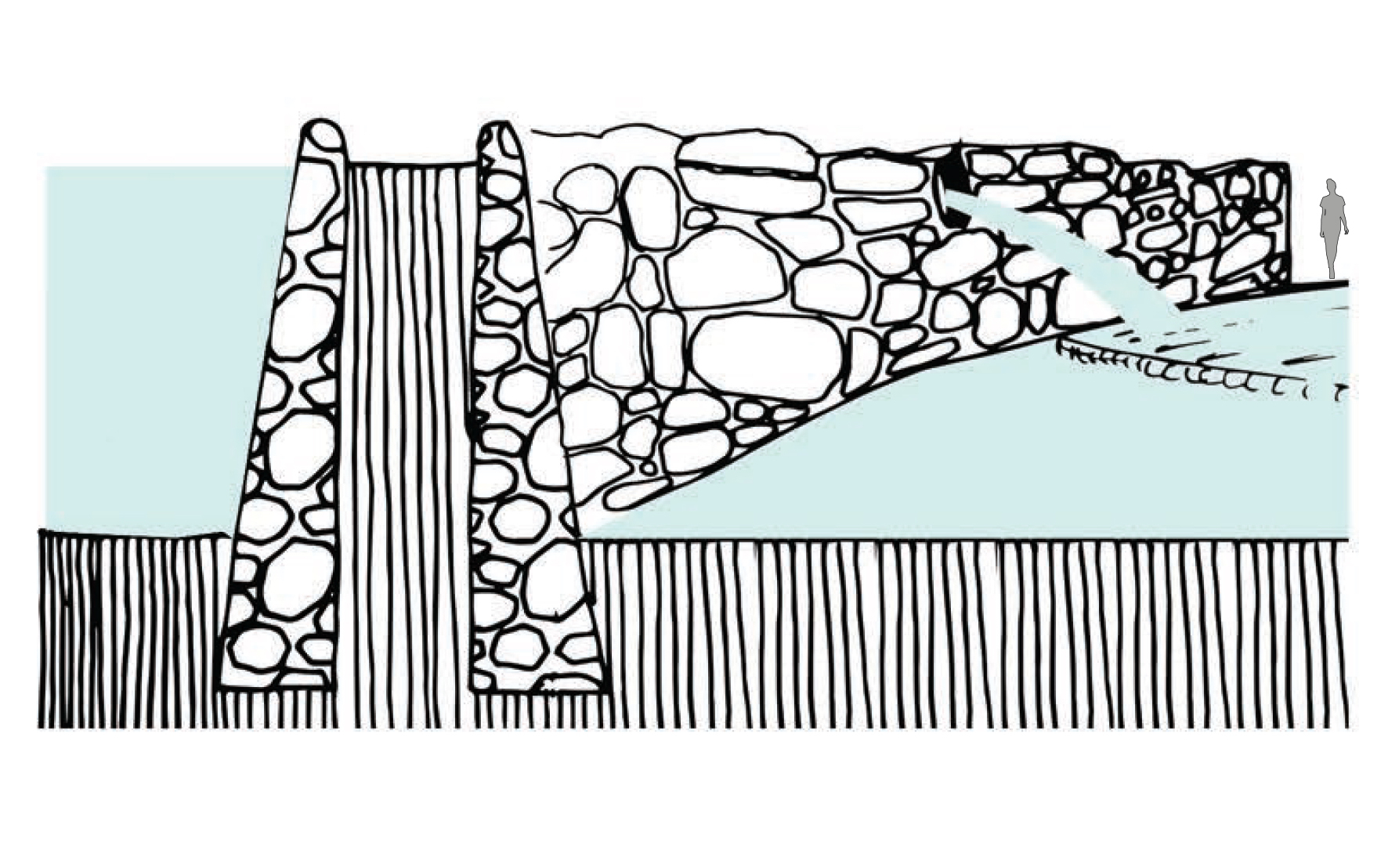

During the planning of the city, special attention was given to the water supply system. With half of the city surrounded by the hills, the city took advantage of various rain catchment areas that were available for storage direct response to local geophysical conditions.

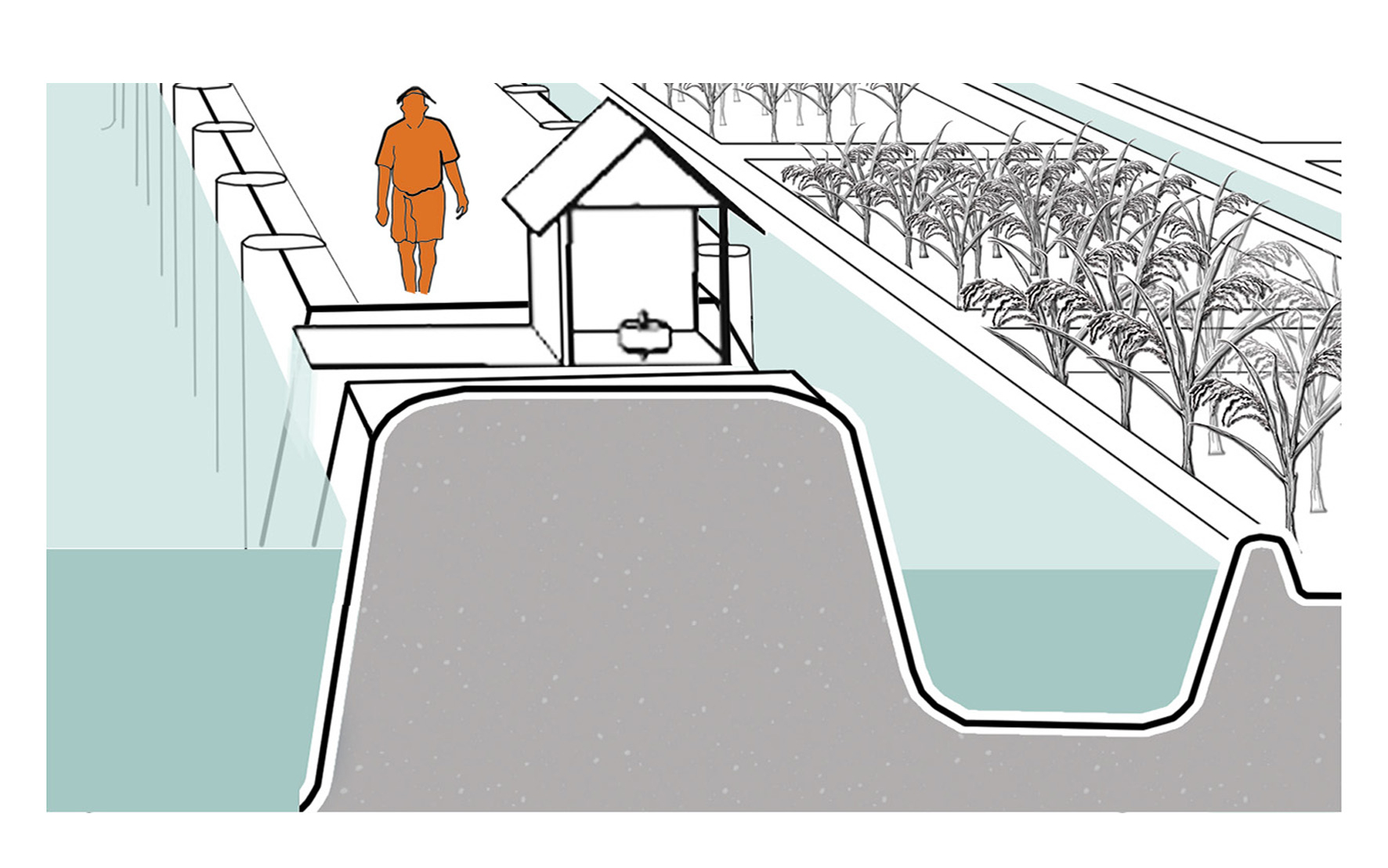

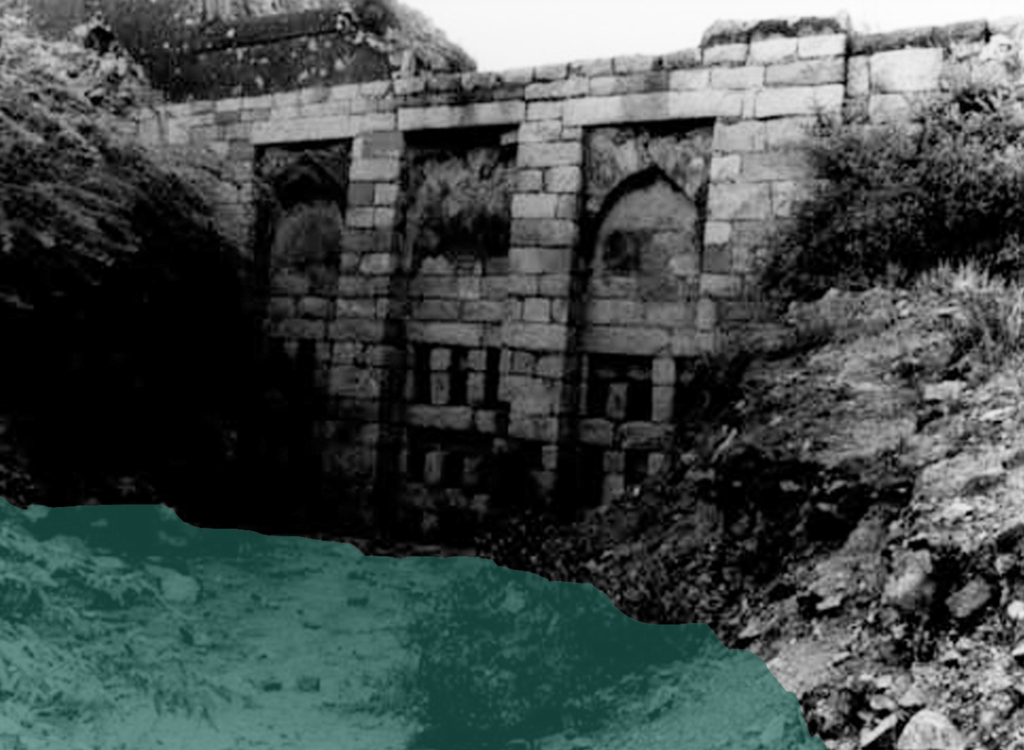

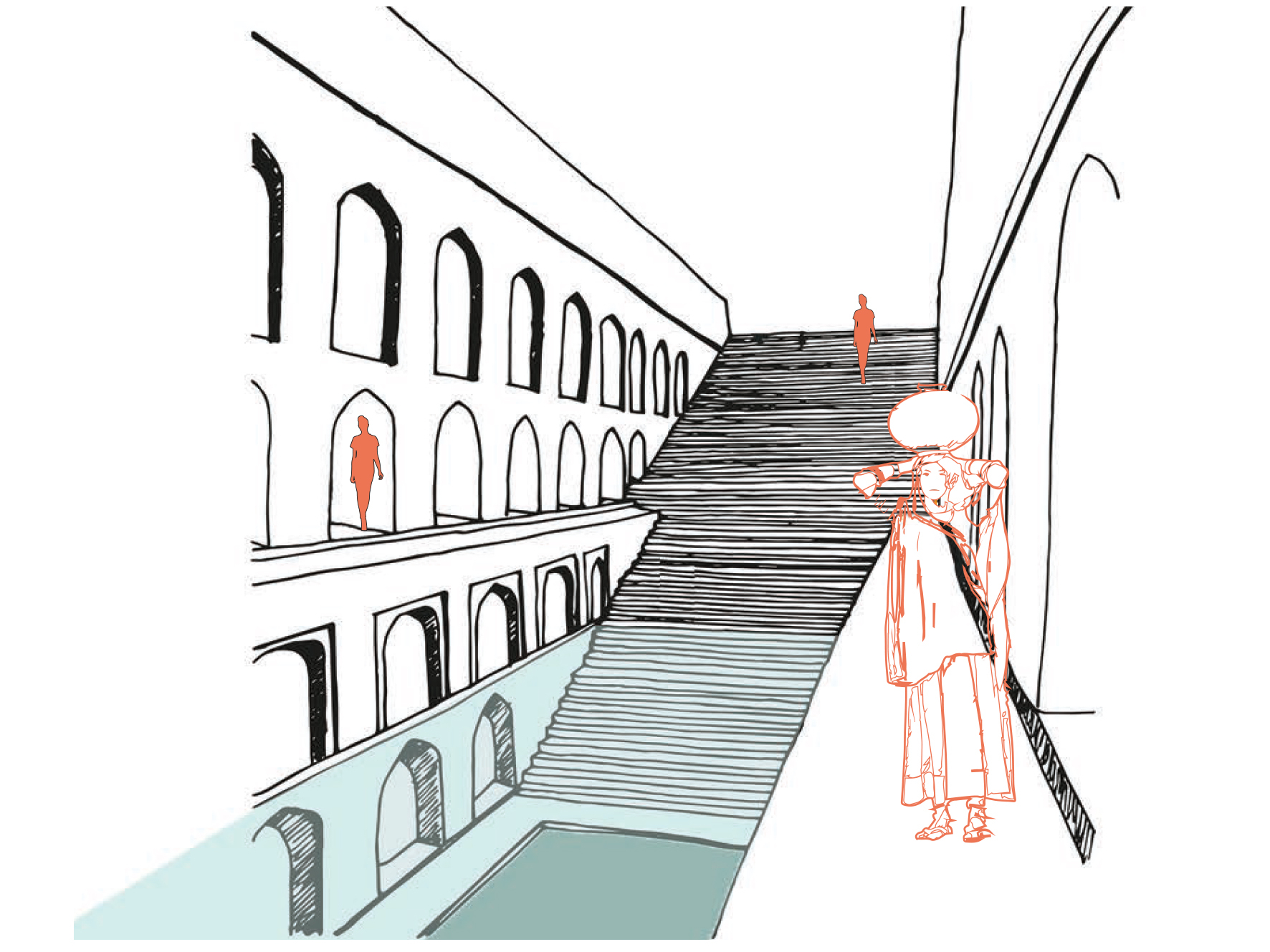

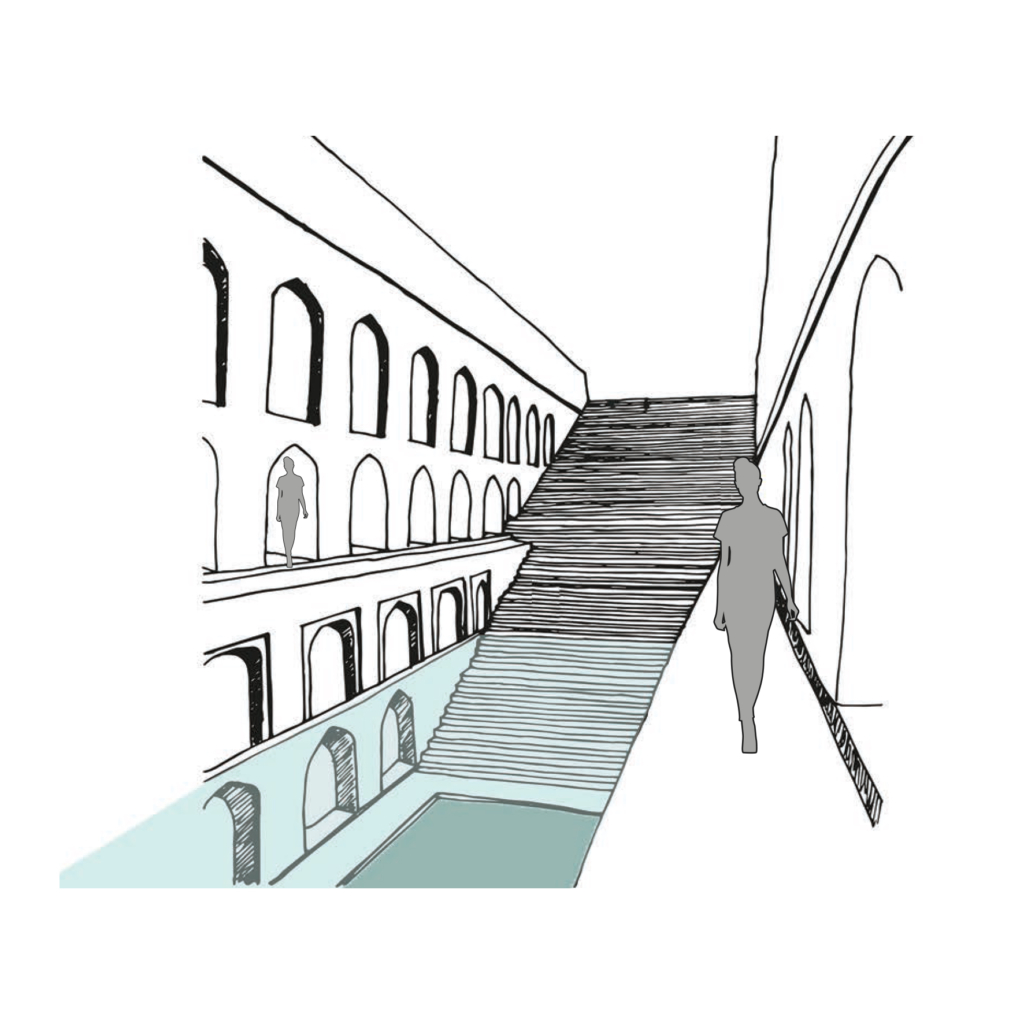

The ruler built 16 miles long canals from the nearby river streams and brought water to the city through aqueducts, As the city grew with increased demand for water, a dam across the river of Dhravyavati was constructed in 1844 along with a canal which runs east to west of the city, wide enough for 5-7 horsemen to ride abreast. This covered canal would then distribute the water through various channels and wells across the city and open at some places for direct access. However, after the construction of the metalled roads and new pipe system of supply, the canal got buried within the markets and its deep walls got filled up.

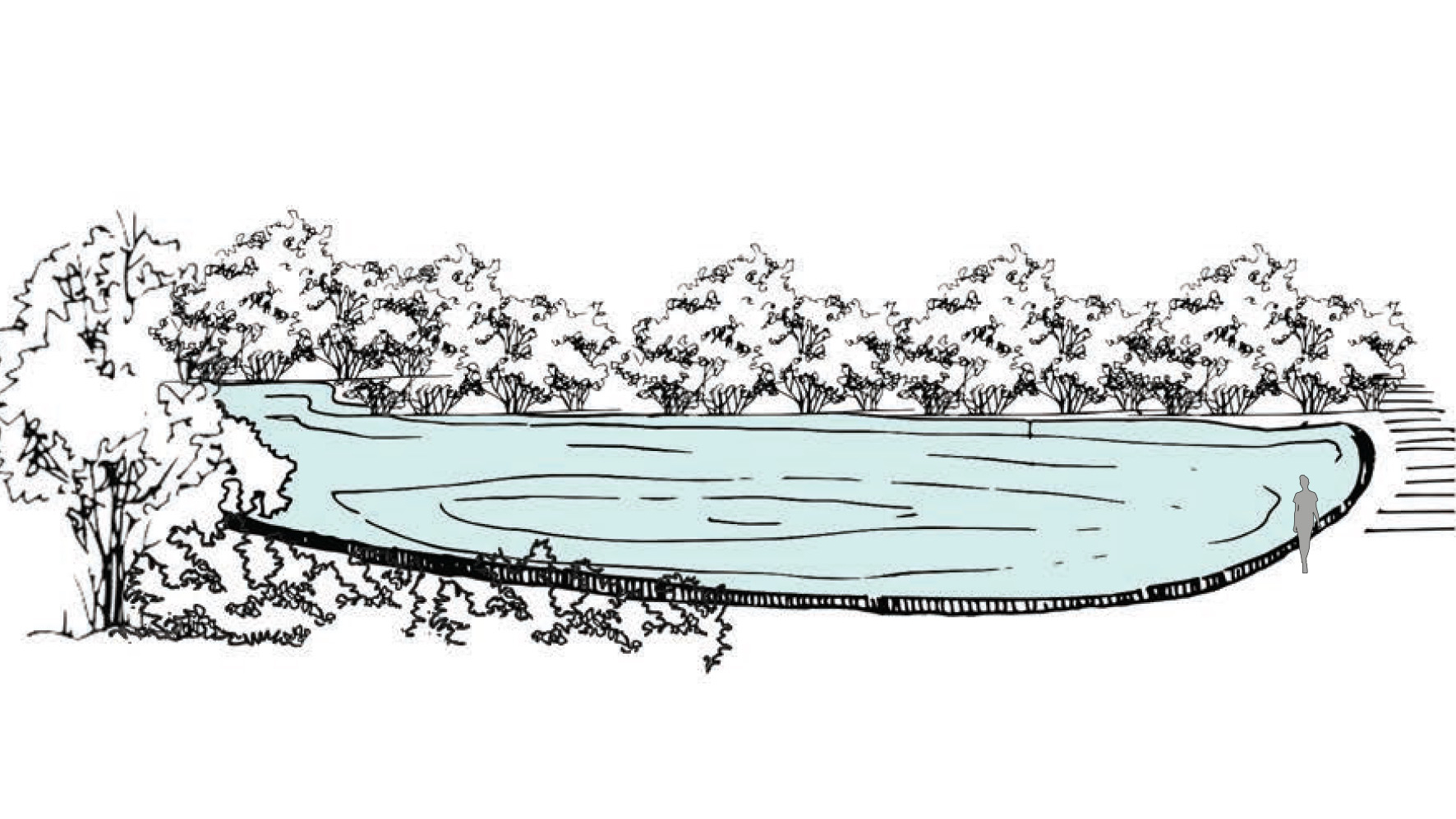

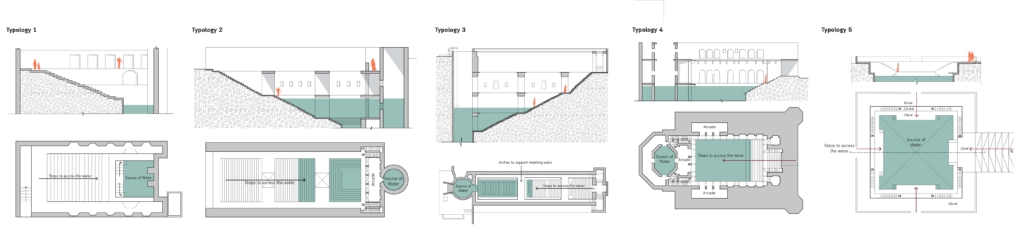

Water has a special significance in Hindu mythology, believed to be as a boundary between heaven and earth. For centuries, stepwells and stepped ponds, also known as Bavdis, Bawadis, Baolis or Vavs, have not just played a significant role in functioning as traditional water systems, serving the community through generations but also as hotspots of social, cultural and touristic interactions. “While various water structures such as tanks, cisterns, paved stairways along rivers (ghats) and cylindrical wells are found elsewhere in India, stepwells and stepped ponds are indigenous to semi-arid regions of Gujarat and Rajasthan” (Livingston & Beach, 2002).