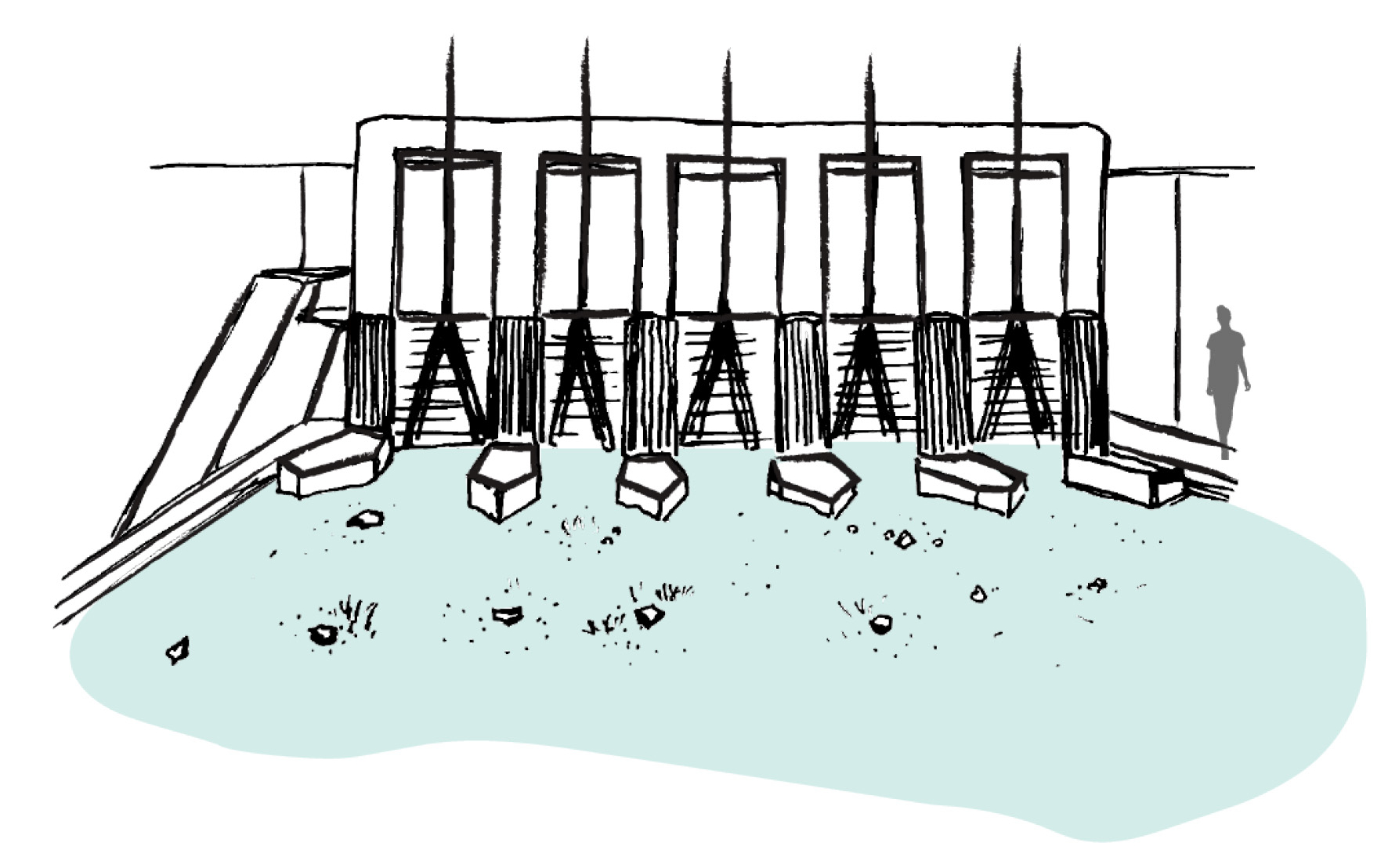

A large-scale water project built in ancient China and used up to now. It can be divided into two systems: the irrigation head and the irrigation water network.

Zhiyun Zhang

2023

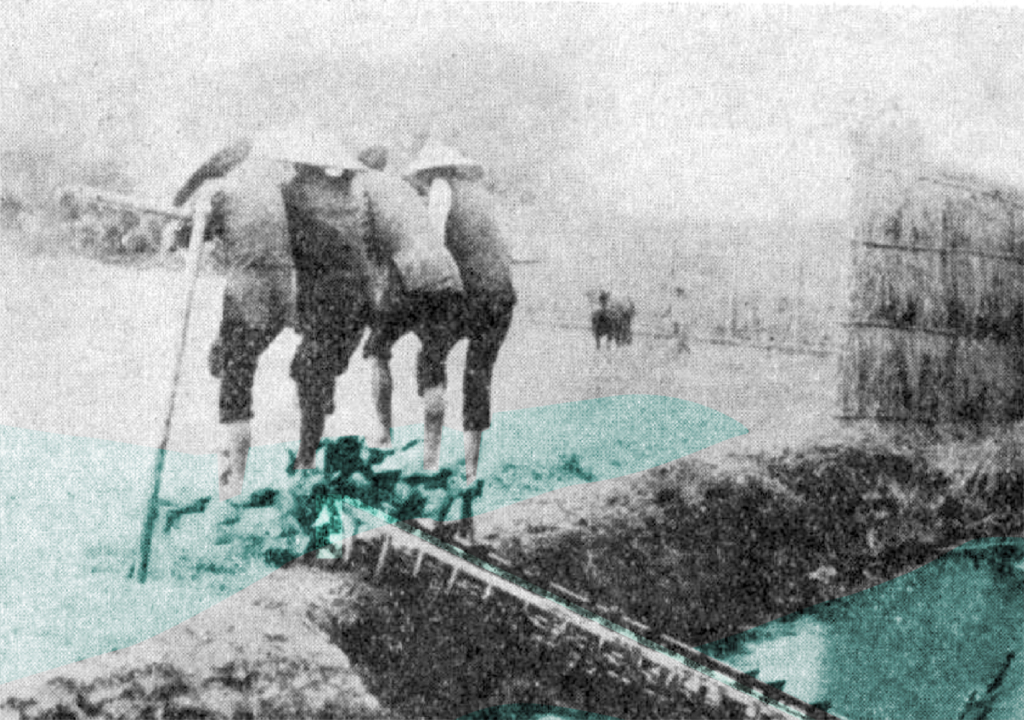

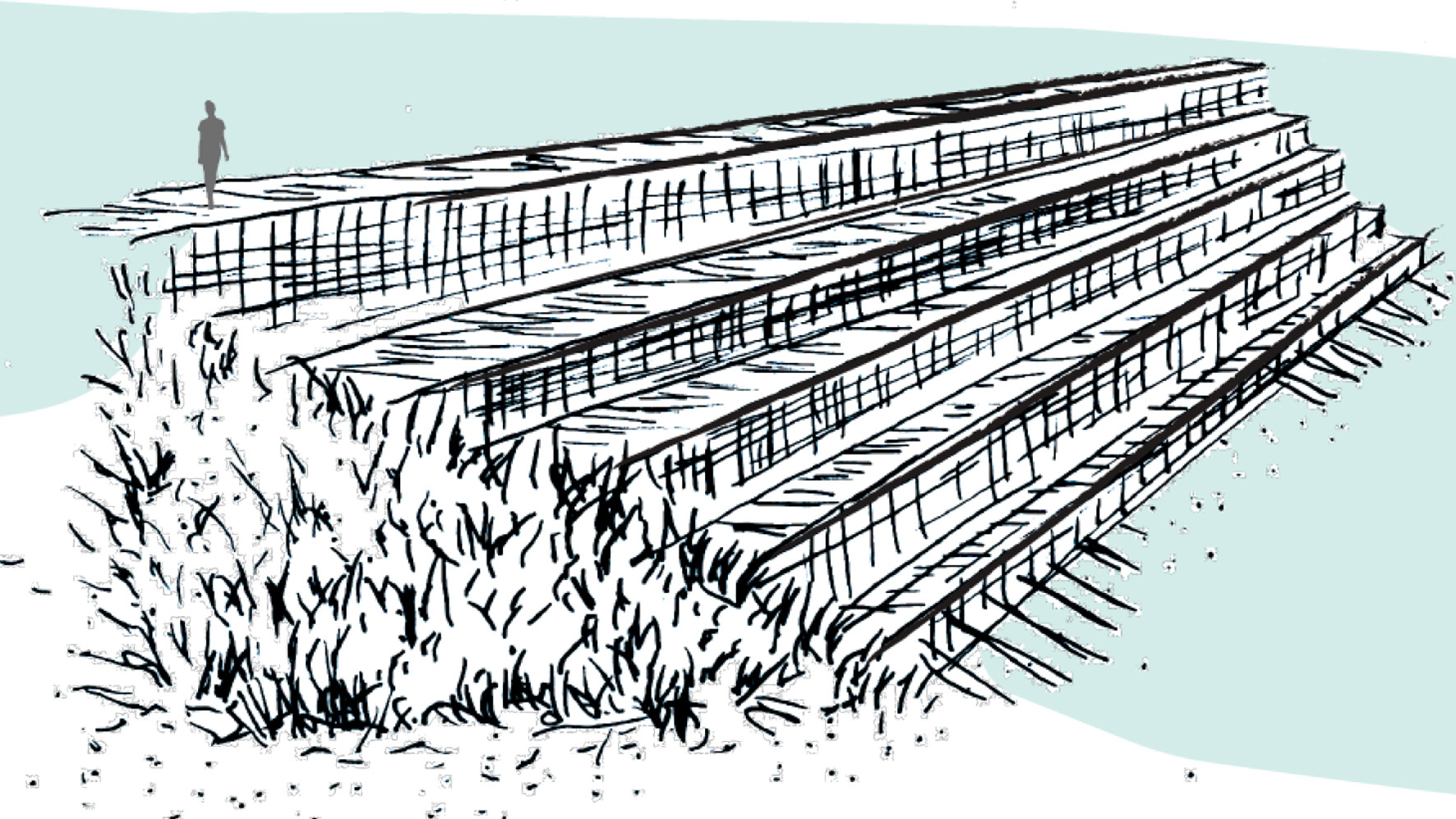

Dujiangyan system is a large-scale water conservancy project built in ancient China and sed up to now. It is located in the west of Dujiangyan City, Sichuan Province, 340 kilometres upstream of the Minjiang River. According to legend, Dujiangyan was built from about 256 BC to 251 BC. After successive renovations, it has played a huge role for more than two thousand years. Without destroying natural resources and by making full use of natural resources to serve human beings, the project turned harm into benefit and made a high degree of harmony among people, land and water, which is also a great “ecological project” in the world.

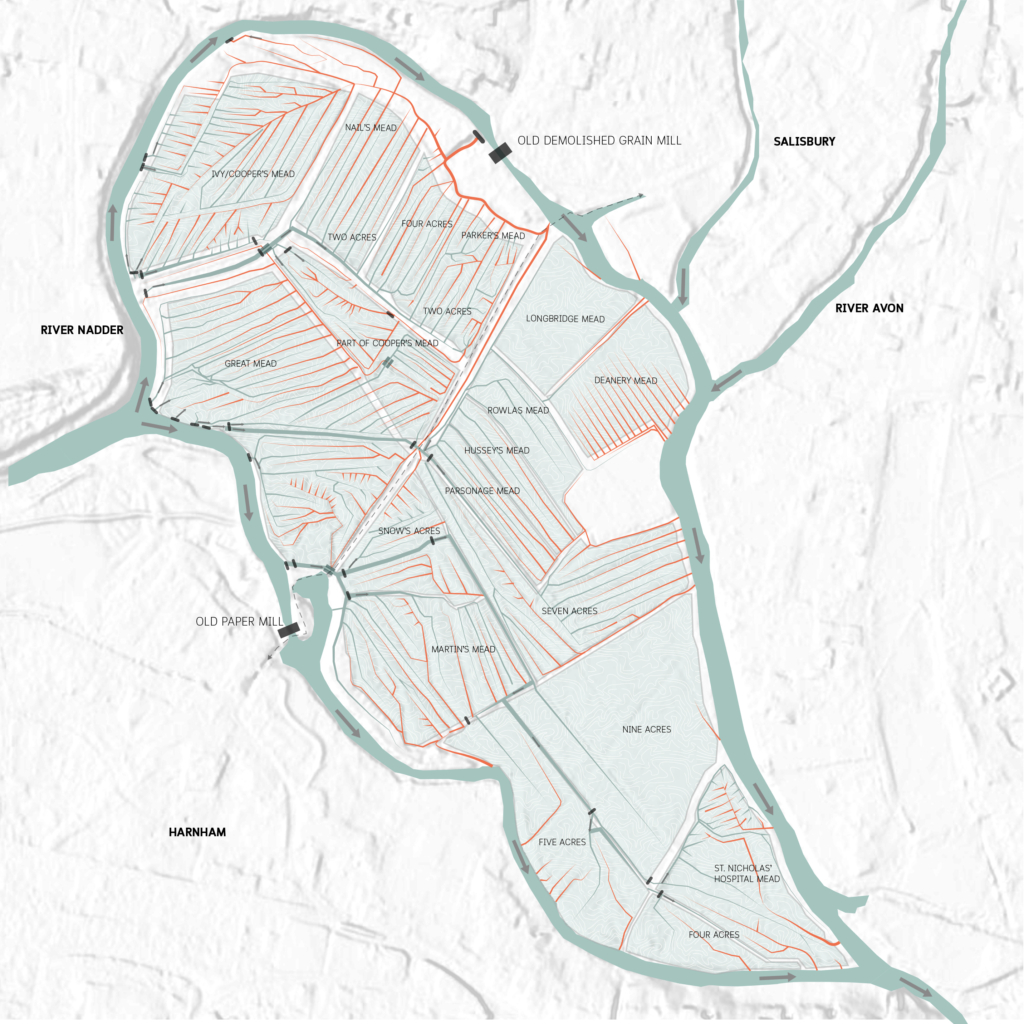

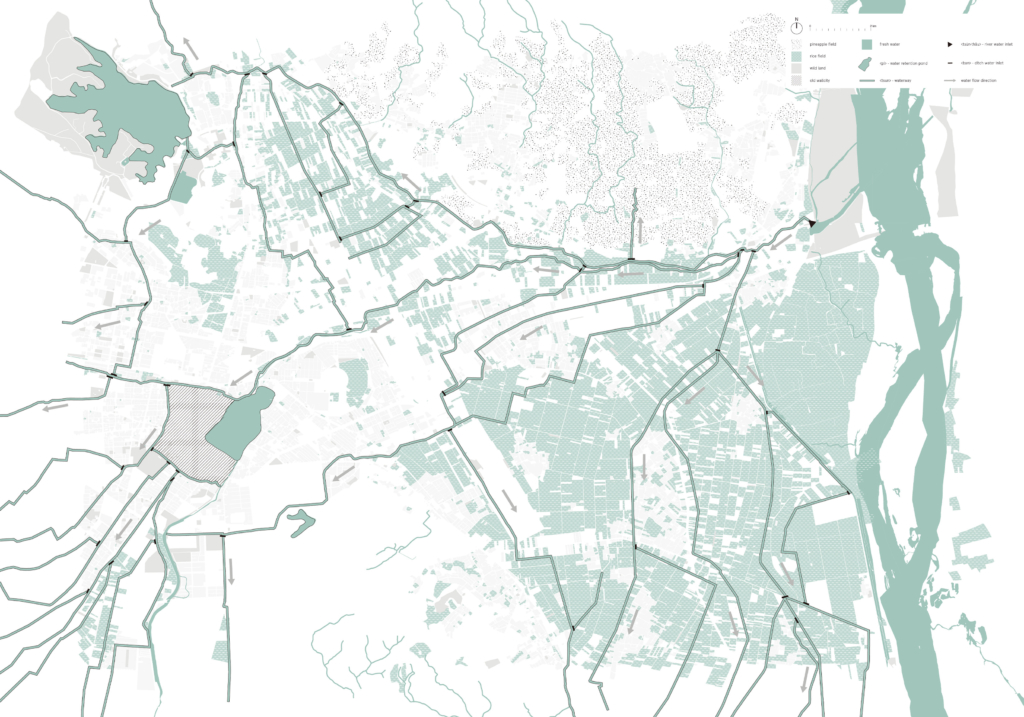

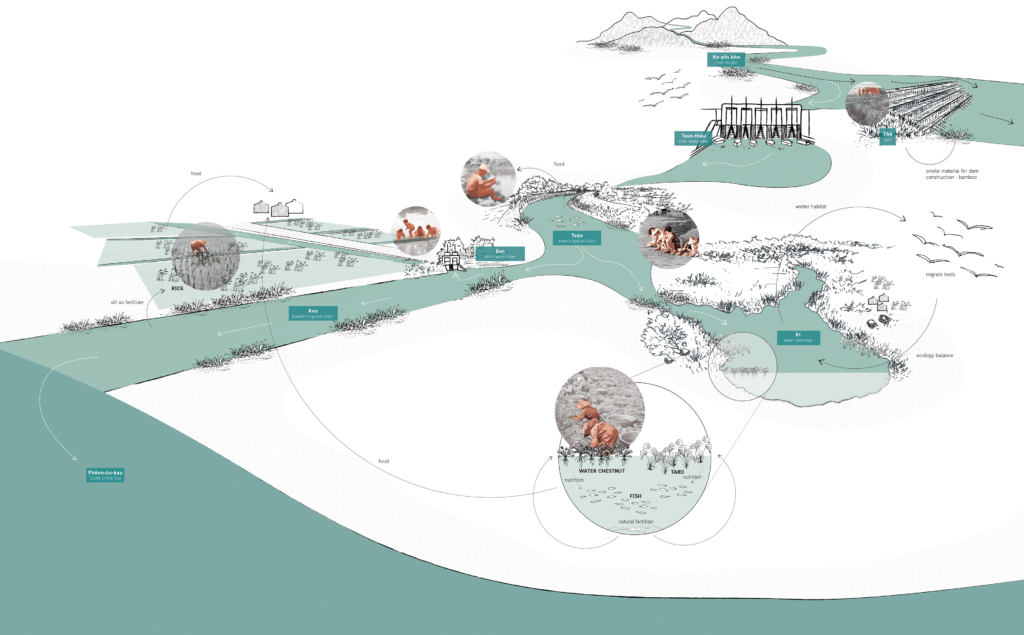

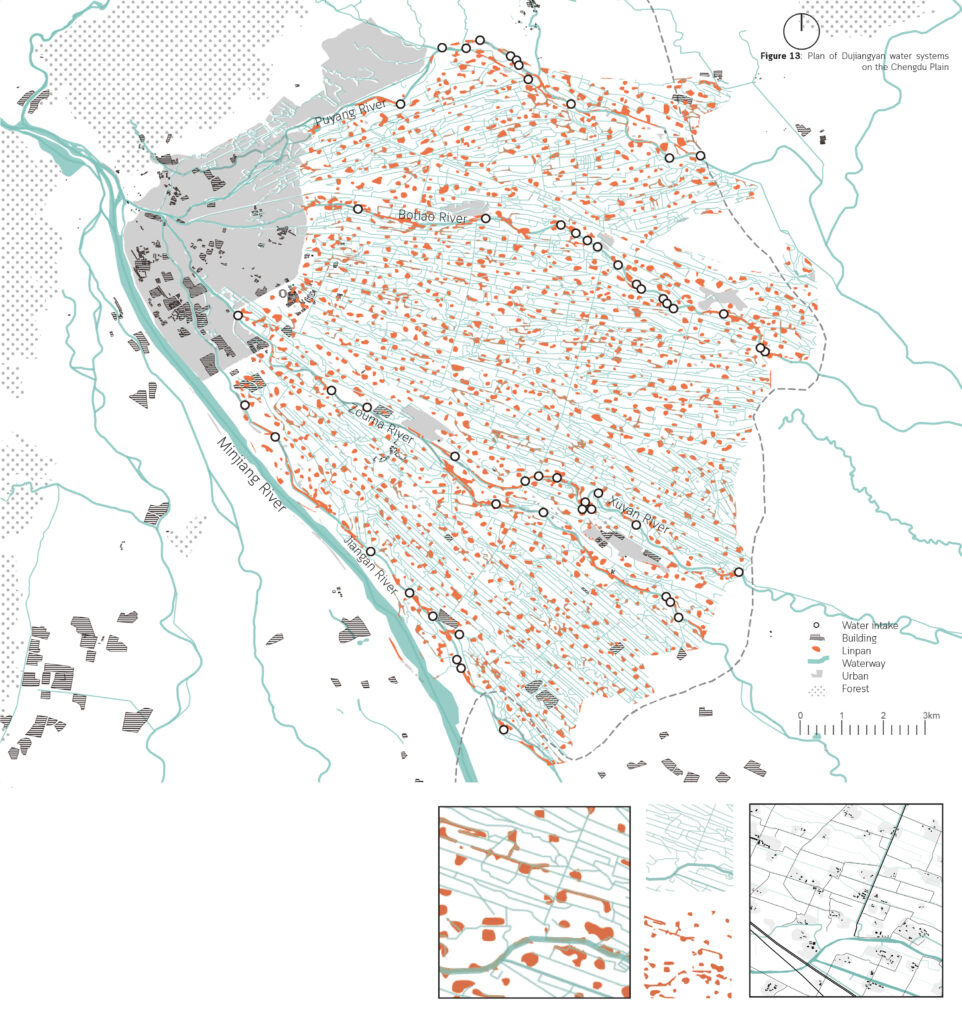

Seasonal rainfall makes the lower-reach places very dependent on the upstream Minjiang River water source. As a unique agricultural and rural landscape, Dujiangyan Project had a profound influence on the production and life of downstream residents, as well as the shaping of the Chengdu Plain in terms of spatial form. This downstream map shows the pattern and textures of the plain, which also explain the inner relationship between the water system, function, spatial form, etc.

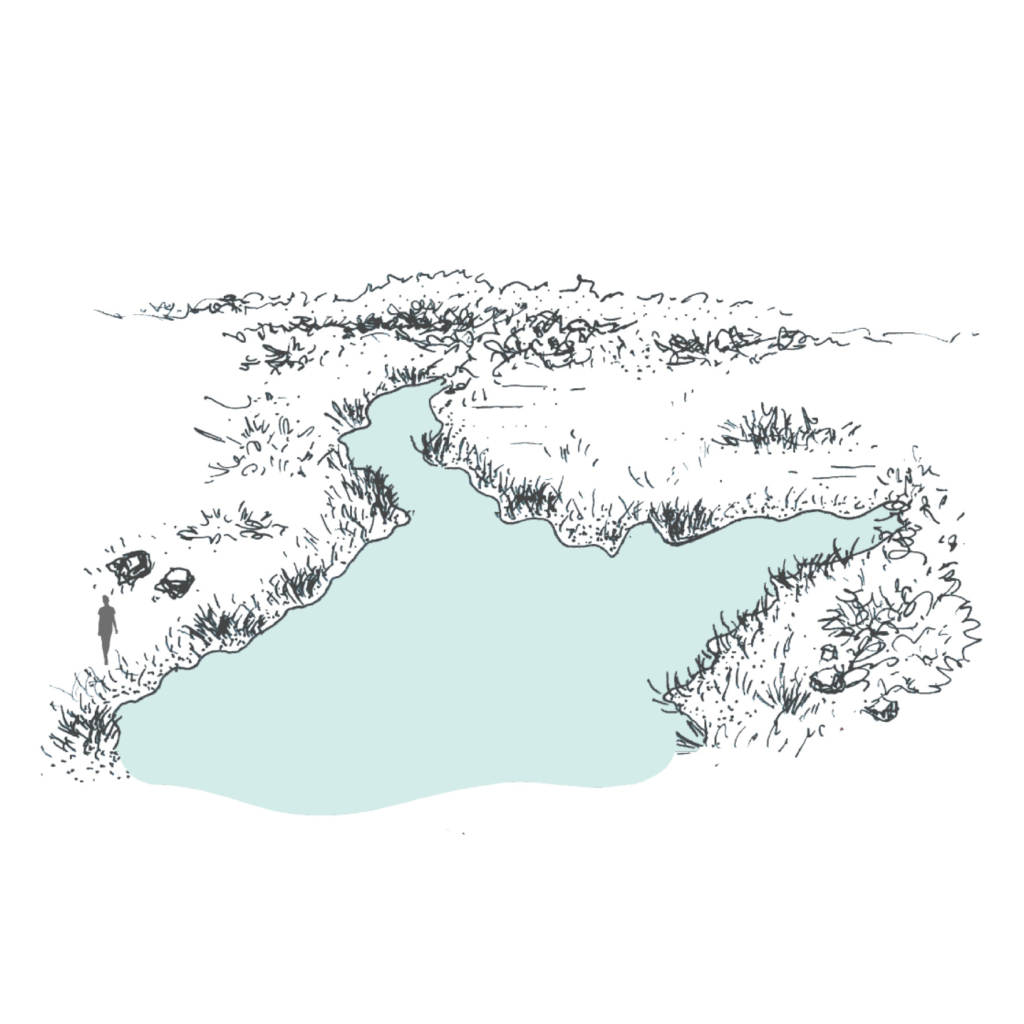

If we zoom in a little bit, the basic pattern of this plain will become more clear, which is consist of lines and blocks. The line is the waterway and the block is the Linpan settlement. It looks just like the blood structure of the human body, oxygen is transported to every cell structure through arteries, veins, and capillaries.

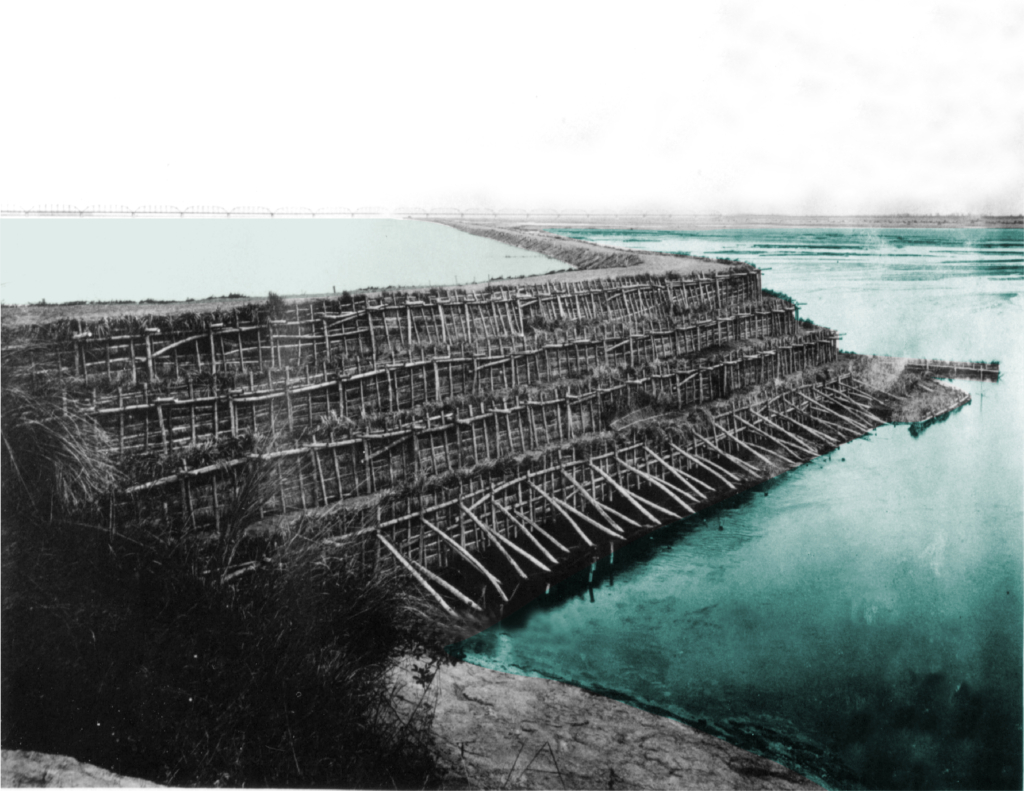

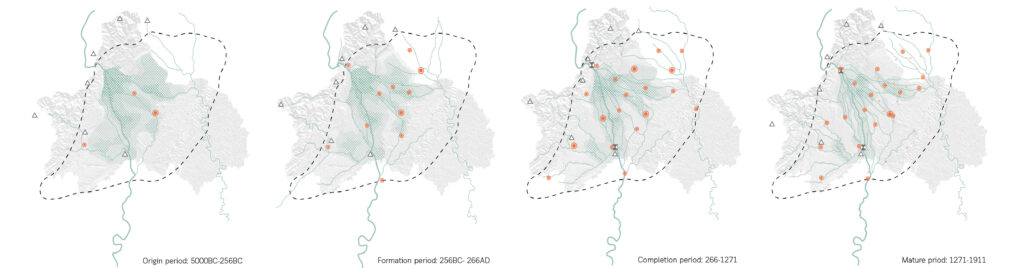

During the origin period, the embryonic form of the water system in the Chengdu Plain is emerging, however, the main rivers are in a disorderly radial pattern and changed frequently. The tributaries didn’t form fixed and stable waterways, bringing several floods and droughts.

Since 260 BC, the construction of the Dujiangyan Water Conservancy Project completely changed the water control environment in the Chengdu Plain, significantly reducing flood frequency and severity, and improving agricultural irrigation efficiency. The water system in the Chengdu Plain mainly expands to the east, and the channels gradually became fixed and clear with the maintenance of residents. The overall shape of water systems gradually becomes a dendritic water network. The opening up of inner and outer rivers provided sufficient water resources for the construction and economic development of Chengdu City. With obvious transportation advantages, there was a rapid development of Chengdu’s urban economy and a dramatic change in town form and layout. According to the maps, the number and range of cities and towns increased significantly over time, while flooding, conversely, decreased with the gradual development of water systems.

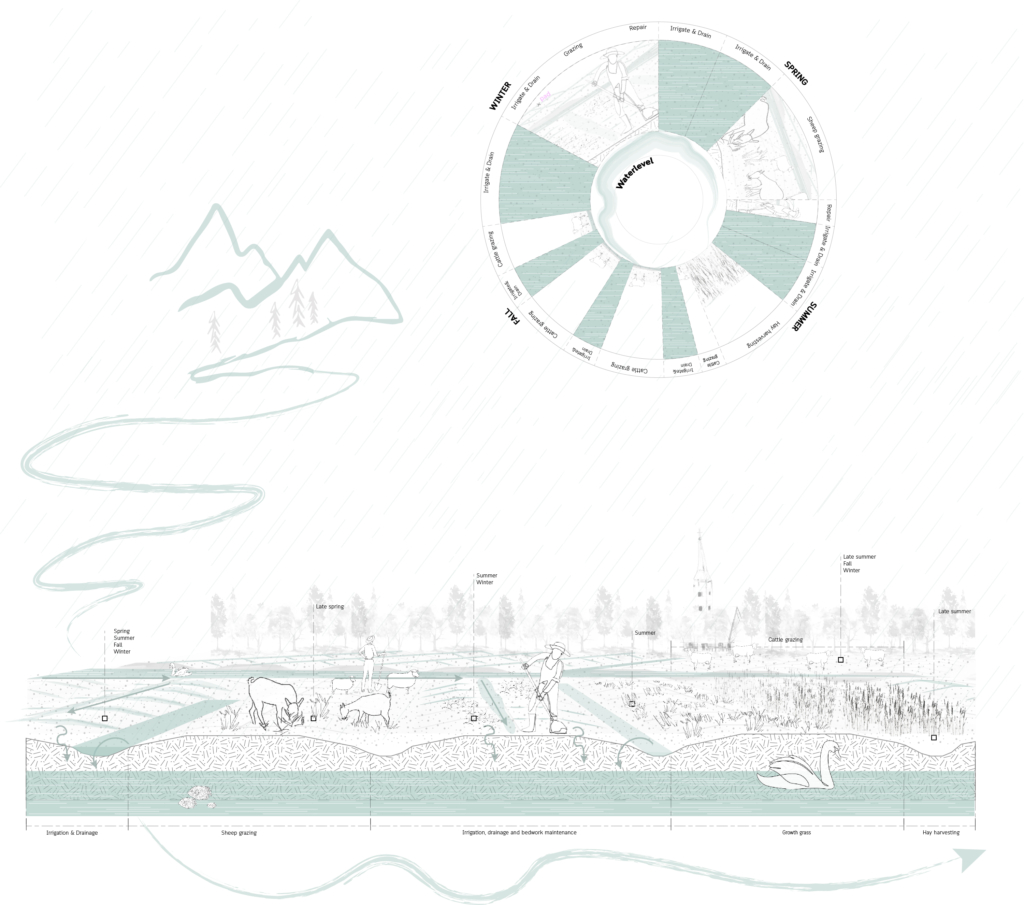

The human activities in the upper and lower reaches of Dujiangyan present different features because of having different main functions. At the head of the Dujiangyan Project, surrounded by green mountains and green waters, the superior ecological environment and historical sites make it a leisure and tourist attraction in addition to undertaking the function of water conservancy regulation.

Circular Stories

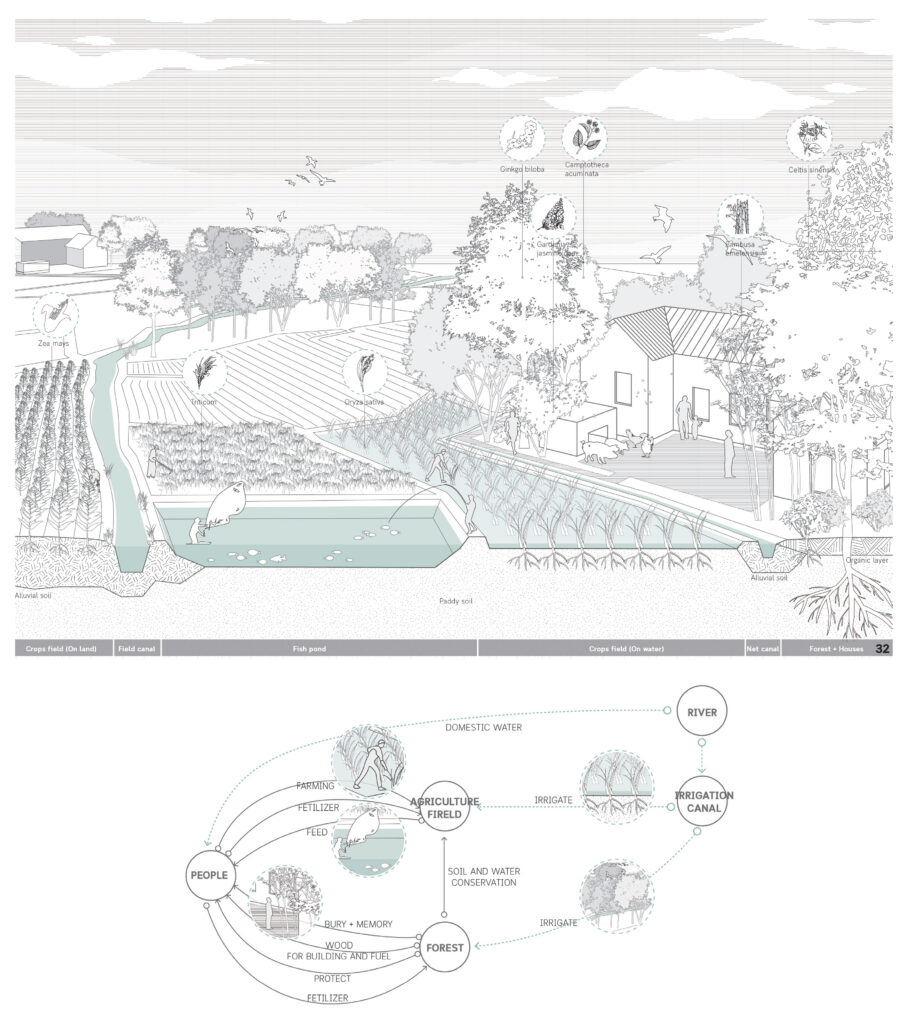

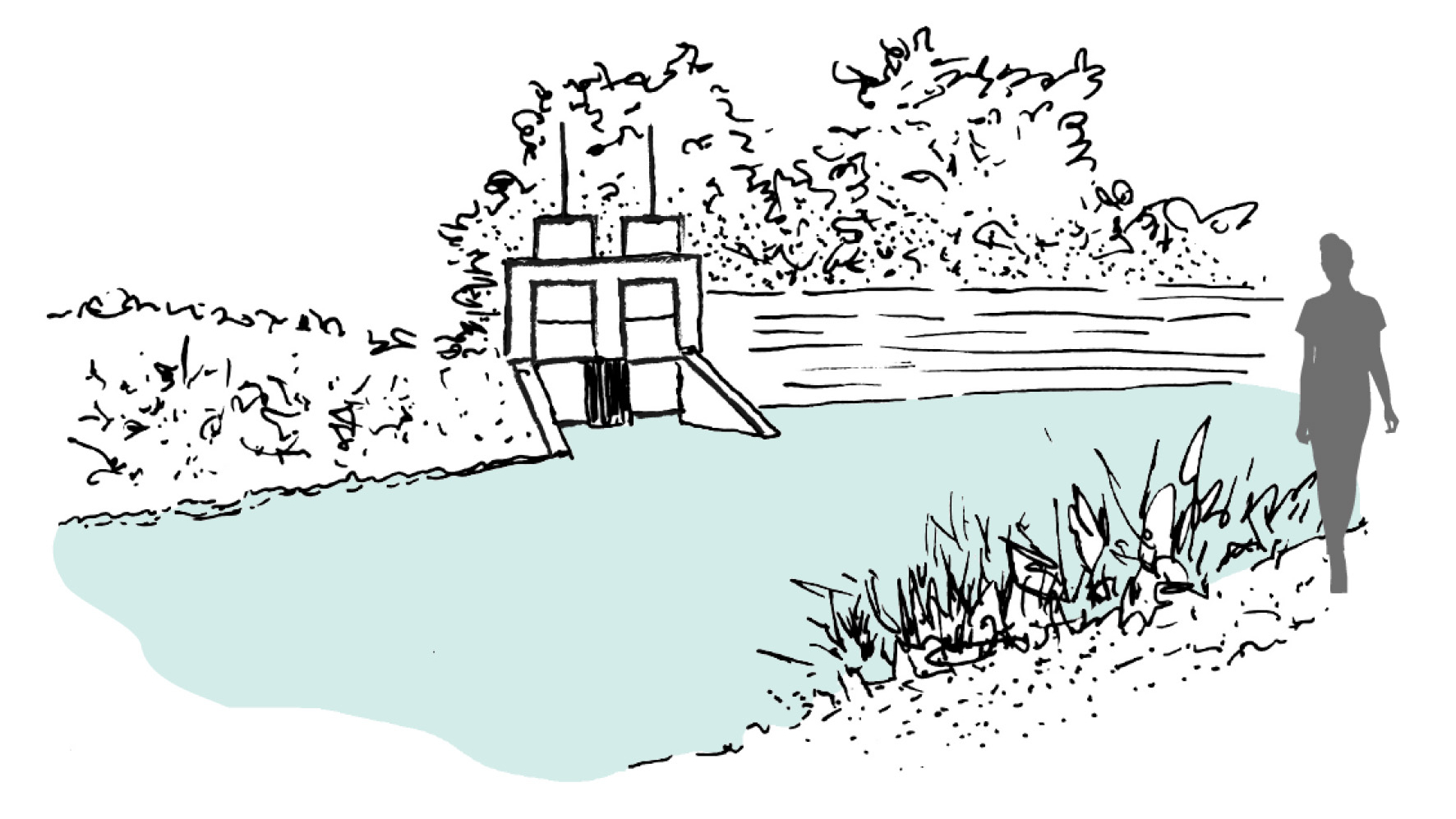

Linpans on the western Sichuan Plain consisting of the Dujiangyan irrigation system, agricultural production, and family-based lifestyle, is a spatial form that perfectly combines cultural symbols and usage values. It is a sustainable system that integrates the living, production and ecological environment of the Chengdu Plain. The ecological farming pattern is in harmony with the farming conditions, traditional farming methods and living needs of the western Sichuan Plain. The entire West Sichuan Plain irrigated by the Dujiangyan Project is a semi-artificial and semi-natural wetland ecosystem, providing habitat for birds and food base and living space for humans, while the symbiosis of human and forest in the Linpan continues to this day. These spontaneous ecological ways of living are worthy of human inheritance and development. Within the Linpan system, people, fields, water and forests are interdependent. For example, people use the wood of forests to make fires and build houses. The forest serves as a barrier and a place for people to rest. Human and livestock manure will in turn fertilize the forest. In this way, Linpan forms a whole circular system of energy, and material, (maybe emotion). People can live self-sufficiently in Linpan.